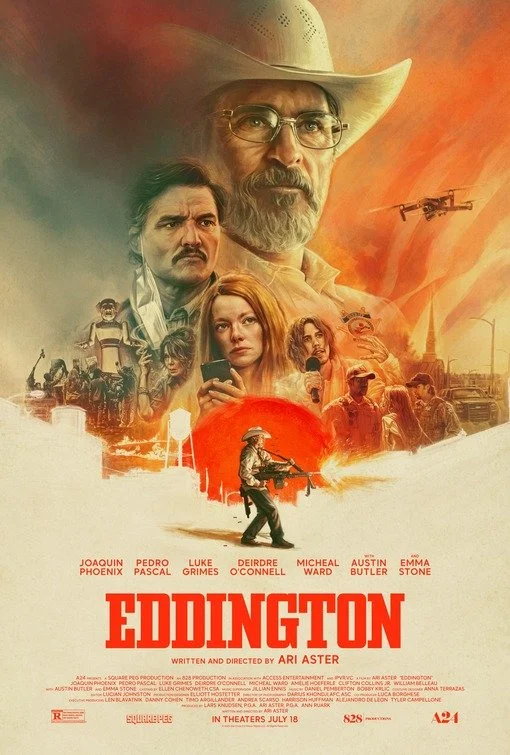

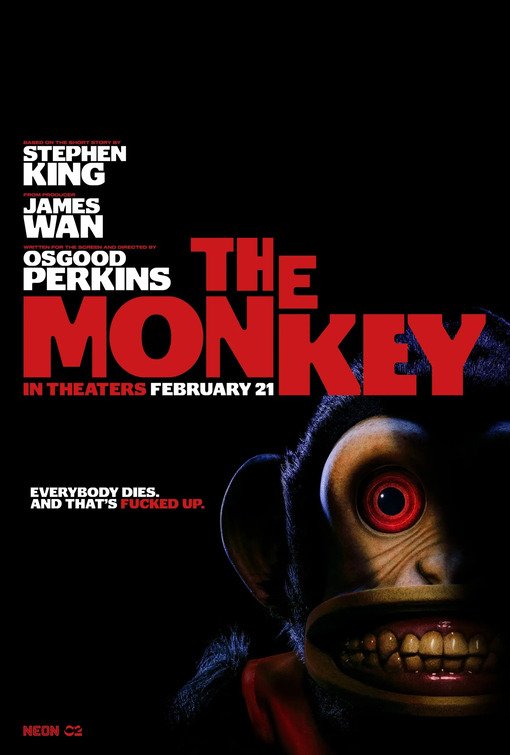

My newest film reviews are now available at The Take-Up. Clicking on one of the posters above will take you directly to the applicable review.

These will be continuously updated so that the most recent reviews always appear in this pinned post. As always, you can also browse all my reviews, across all publications, in this site's index, which is organized alphabetically by film title.

Beginning October 6, 2017, posting here at Gateway Cinephile will be reduced significantly. Fortunately, the reason for this is Good News rather than Bad: Effective that same date, I will be serving as the lead film critic at The Lens, the blog of Cinema St. Louis. CStL is a non-profit organization dedicated to promoting the art of cinema. In that capacity, they produce several annual film festivals and other film-related events in the St. Louis metropolitan region, including the St. Louis International Film Festival, the St. Louis Filmmakers Showcase, QFest, and the Robert Classic French Film Festival.

I have long had a positive relationship with CStL, and when they requested that I come on board as the primary contributor to their re-launched official blog, I didn't have to think about it very long. They have graciously offered me a great deal of editorial freedom, allowing me to set my own assignments and essentially write about whatever piques my interests. Full disclosure: I will also be providing other services to the organization, including assessment of festival entries.

This new position potentially creates a substantial overlap with Gateway Cinephile, as almost anything I might post here could also be posted at The Lens, where it would reach a much wider audience. Accordingly, the flow of new content at Gateway Cinephile will be slowing to a virtual trickle. Occasionally, I may post pieces here that are not a good fit for the Lens, for one reason or another. Regardless, I will continue to maintain this blog in its present state, and to update the indices (linked above) of my reviews and other writing, if only for reference purposes. Needless to say, I will no longer be writing regular weekly reviews for St. Louis Magazine, although I will continue to contribute to that publication (and others) on an intermittent basis.

Thank you to everyone who has followed my work for the past decade, and to the handful of future visitors who will inevitably stumble onto my older writings. (Four years later, this essay on The Dunwich Horror continues to pull in a major chunk of this blog's traffic, for some inexplicable reason.) I have inaugural reviews up at The Lens today, so please adjust your bookmarks and join me there.

The odds were stacked against director Michael Verhoeven’s horror feature Friend Request from the beginning. The film is a German production shot in South Africa with a stable of English-speaking actors. Combined with a sub-$10 million budget, that Frankenstein provenance results in a predictably non-specific setting. It’s implied that the film unfolds in a posh Southern California coastal city, but the necessary geographical caginess and the generally chintzy production values give the whole enterprise a glum air of disposability. The film’s zeitgeist-pandering central conceit—a Facebook-mediated haunting—not only promises tedious Luddite moralizing and kludgy imitations of post-Millennial slang, it’s also virtually guaranteed to age poorly. Indeed, Verhoeven’s feature was shot in 2014, and given the present pace of Internet culture's evolution, it already feels faintly dated, a relic from the hoary days of the Ice Bucket Challenge, the potato salad Kickstarter, and “Let It Go” parody videos.

It’s therefore pleasantly surprising that Friend Request isn’t a complete pile of dogshit. Sure, it’s inarguably lazy, recycling plot beats and design elements from 20 years’ worth of American J-horror clones. It’s stupid as hell, weighed down by a screenplay replete with tin-eared corporate approximations of How Kids Talk These Days. Perhaps most obnoxiously, the film proffers precisely the smug messaging suggested by the trailers: Anyone who is introverted and socially awkward must be a murderously insane necromancer, especially if their personal aesthetic can be described as "black and slightly darker black." Still, Verhoeven’s film is low-rent ghoulish fun, and even intermittently inspired in terms of its visual and sound design. For all its insipidness, Friend Request is rarely outright boring, and whenever it briefly lurches from Entertainingly Bad Movie to Annoyingly Bad Movie, it generally rights itself with its schlocky, R-rated haunted house shocks.

The scenario is pure thirty-second studio pitch material, and if one has seen the trailer, one already knows everything essential there is to know about the plot. Sophomore psychology student Laura (Alycia Debnam-Carey) is pretty, outgoing, and popular, as evidenced by her 800-plus Facebook friends. (The film is never entirely clear whether the social media friend count as a yardstick of personal success is meant to be taken satirically or not, although given the screenplay’s overall brainlessness, one suspects the latter.) Laura lives off-campus with her flamboyant friends Olivia (Brit Morgan), Isabel (Brooke Markham), and Gustavo (Sean Marquette). She is currently dating handsome surfer and medical student Tyler (William Moseley), and rounding out her immediate social circle is tattooed computer geek Kobe, who, not incidentally, harbors an unrequited crush on Laura.

One day an offhand smile at her reclusive classmate Marina (Liesl Ashlers) nets Laura a Facebook friend request. Marina is something of an amateur video artist with a goth bent—her timeline is dense with ravens, dead trees, and severed doll heads—and Laura initially takes a shine to her talent, even though the girl has (gasp!) zero Facebook friends. Laura accepts the request, but in short order she regrets that fateful click. Marina is needy and aggressively unctuous, bombarding Laura with posts and direct messages as though they were suddenly best friends. When Laura lies about her birthday party to spare Marina’s feelings, the latter girl unsurprisingly spots the evidence on Laura’s timeline, resulting in a public confrontation and virtual unfriending. This proves to be too much for the fragile Marina, who subsequently commits suicide by hanging and self-immolation, filming and auto-posting this final act online.

A little thing like death isn’t much of a deterrent to a truly determined cyber stalker, however. It turns out that Marina’s ritualistic suicide is the opening move in an elaborate revenge plot against Laura, a scheme that seems to have two prongs. First, Laura’s friends and family are soon plagued by terrifying hallucinations, most of them involving swarms of black wasps, a pair of mutilated boys, and a decrepit, demonic incarnation of Marina’s spirit. These visions gradually drive the people in Laura’s immediate social circle to commit suicide, one by one. Meanwhile, Laura’s Facebook profile is hijacked by a mysterious presence, which proceeds to post videos of her friends’ gruesome deaths and otherwise make her look like a horrible person. Laura swiftly finds herself under investigation by university and police authorities, and—the horror!—ostracized by outraged Facebook friends, who abandon her in droves. (Her steadily dropping friend count recurs as an animated, on-screen flourish.)

The most vexing thing about Friend Request’s plot is that it feels like a missed opportunity for a much more ambitious and ruthless horror film. At risk of indulgently imagining the story that might have been, Verhoeven and co-writers Matthew Ballen and Phillip Koch could have easily expanded Marina’s death list to include everyone on Laura’s friend list, instead of confining the ghost-driven suicides to her closest pals. The ghastly spectacle practically writes itself: montages of dozens of suicides, from the crude to the baroque, as the 800-plus digital connections Laura has made become the proverbial mark of damnation. (And fuck you, Friend Request, for eliciting this thought: The Happening did it better.) The mass exodus from her friend list would thereby take on the urgency of a hysterical mob fleeing a burning building, rather than, say, the mere disgusted unfriending of an old high school classmate with a pro-Trump meme on their timeline.

Verhoeven is primarily interested in hewing to the template of a slasher-informed vengeful ghost story, bumping off Laura’s closest friends one at a time in spooky set pieces laden with jump scares. Laura’s pals are little more than hastily sketched clusters of attributes, and as such the hallucinations that Marina inflicts on them aren’t custom-tailored in any meaningful way. She just relentlessly pummels them with spectral shocks, reducing each person to a frazzled, hollow-eyed wreck who ultimately surrenders to the hypnotic lure of death. It’s an unimaginative but solid enough approach to the story, and Friend Request benefits from the director’s facility for said jump scares, which feature enjoyably off-kilter timing, potent sound design, and some creepy digital and makeup effects. It’s pedestrian as can be, but executed skillfully enough to be grisly fun rather than a dreary slog.

Nothing about Friend Request stands out as truly memorable, but there are stimulating flashes in the story and design that lend the proceedings some vigor, at least in the moment. The underlying occult conceit is admittedly clever, positioning the blank computer screen as the 21st century version of a diabolist’s black scrying mirror. The second half of the film essentially follows The Ring’s road map, as Laura and Kobe dig into Marina’s troubled history and try to determine the secret location where she filmed her suicide. Fortunately, these Nancy Drew passages compliment rather than water down the hallucinatory set pieces, and Verhoeven blessedly resists wedging a contrived, late film twist into the secrets that Laura uncovers. (There is a third act plot swerve, but it’s both plausible and neatly foreshadowed while still managing to shock.) The film makes liberal use of the animated pop-ups that have become a mainstay of post-iPhone filmmaking, but it does so with a fleet, almost impressionistic sensibility that doesn’t visually distract. Occasionally, the filmmakers even deliver some downright marvelous aesthetic touches, such as the way that Gary Go and Martin Todsharow’s score suggests the distinctive sound of cellular interference with audio equipment whenever Marina draws near.

When one moves beyond the proximal scares and formal polish and into the underlying thematic territory, however, Friend Request starts to unravel. Given the speed with which Laura’s online friends huffily abandon her, Verhoeven and his co-writers seem to be commenting on social media insta-outrage and the fickleness of the Internet mob, but what exactly that comment might be is anyone’s guess. The film’s overall ethos has a whiff of lazy cynicism. Broadly speaking, Friend Request seems to proffer a facile anti-technology pessimism, the same sort of tongue-clucking that drives countless, insipid “Are We Addicted to Social Media?” think pieces and (ironically) hand-wringing memes about Kids Today and their damn smartphones. Yet the film’s attempts to critique and satirize digital culture are clearly half-hearted, as if Verhoeven doesn’t really buy into this Luddite finger wagging, but is obliged to advance it because of his story’s fundamental premise. (The recent Ingrid Goes West is far more cunning and pitiless about pushing the curated lies of social media to their reductio ad absurdum limits, and it ultimately emerges as a much better horror film, if a stealth one.)

Cheap cynicism is easy enough to overlook in the horror genre, but the most distressing aspect of Friend Request is its absurdly blinkered treatment of anyone who seems strange, awkward, or non-conforming in some way. Verhoeven’s film poses, with a straight face, the notion that introverted weirdos are all deranged, damaged monsters who, if given half a chance, would eagerly use black magic to kill happy, successful, popular people. It’s petty high school bullshit of the crudest sort, rendered downright silly by the film’s conflation of the Movie Version of goth sub-culture (Skulls! Poe! Marilyn Manson!) with the darkest evil imaginable. Paradise Lost should have invalidated such nonsense forever, yet here it seems intended to elicit a shrug or even a nod of agreement.

What’s more, Friend Request advances that Laura’s original sin was not in spurning Marina, but in taking an interest in the clingy, creepy outcast at all. In the film’s conception, any kind of creative expression is a friendship red flag—unless, of course, it generates dollars, fame, and clicks. (It bears noting that Marina creates her animated videos primarily for herself in order to cope with horrible childhood trauma.) Art doesn't count, apparently, unless it's Shared. Ultimately, the film’s perhaps unintentional yet repugnant message is that one shouldn’t even acknowledge someone who lacks Instagram followers, because that person is almost certainly unstable.

[This post contains minor spoilers.]

Earlier this year, it seemed a certainty that Gore Verbinski’s lavish gothic nightmare A Cure for Wellness would be the weirdest wide release from a major studio in 2017, and probably for many years to come, given its dismal box office. As it happens, Wellness’ reign only lasted six months. Director Darren Aronofsky’s mother! is about to be unleashed on an unsuspecting multiplex audience. It’s the kind of film that leaves the viewer dazed and fumbling for words, wondering how it was ever greenlit, let alone brought to life. It embodies the nervy, go-for-broke species of filmmaking that elicits excitement simply by existing. It is also utterly deranged, a work that comes perilously close to being unintentionally funny. For this writer, it did not, but it is perfectly understandable if some viewers gape in disbelief and irritation, muttering “Are you fucking kidding me?”

The less said about the plot, the better, so a sketch of the opening scenario must suffice. In a remote, sprawling house, a middle-aged poet (Javier Bardem) dwells with his wife (Jennifer Lawrence), who is at least twenty years his junior. (In the first of many touches that signal Aranofsky’s allegorical aims, these characters are never named. Taking a page for Antichrist, they are simply listed as “Him” and “Mother” in film’s credits.) Originally His childhood home, the house was mostly destroyed in a fire, but it’s since been rebuilt and refurbished in a faux-rustic style. This remodeling is due to the painstaking efforts of the Mother, who views it as her role to create an idyllic space for her husband’s work. There doesn’t seem to be much of said work going on, however. He disappears for long stretches in between bouts of staring impotently at a blank page, fountain pen in hand. She gives him apprehensive but encouraging smiles, and carries on with preparing meals, doing laundry, restoring furniture, and painting walls.

There are early signs that not all is as it seems in this bucolic world. Some are subtle, such as the curious absence of roads connecting the house to the outside world. (The surrounding landscape is simply a ring of green, rustling grass, giving the house the feeling of an isolated prairie homestead.) Other are less so, such as the Mother's repeated visions of a throbbing, heart-like organ deep within the walls of the house, or the rattling, plaster-loosening thud she hears behind a bricked-up niche in the cellar. Aronofsky gives these early scenes an unmistakable atmosphere of squirming horror. Something is wrong, but what that something might be is maddeningly indefinite, to both the viewer and to the Mother.

The film ruthlessly adheres to the Mother's viewpoint, and in light of the director’s 2010 feature Black Swan, the viewer is naturally inclined suspect that she may be an unreliable protagonist. Pointedly, the Mother suffers from ringing migraines that can only be relieved by imbibing a yellow powder dissolved in water, a solution that doesn’t resemble anything a doctor would prescribe in the 21st century. Nonetheless, it eventually becomes apparent that mother! is unfolding on a stage where the usual horror and thriller twists—she’s dreaming / dead / insane / a computer program / whatever—are rendered irrelevant. Aronofsky is working in the realm of Old Testament nightmare, and, befitting his po-faced storytelling style, he never once reveals his hand or cracks a grin. The optimal way to experience mother! is to assume that what one is seeing is “real,” no matter how batshit it becomes. (And hoo boy, does it ever…)

Eventually, the couple’s isolation is disrupted by the arrival of an older Man (Ed Harris), purportedly a surgeon in search of a bed and breakfast. The poet invites him to spend the night—without consulting with his wife, naturally—and soon the two men are conversing into the wee hours over drinks like old friends. Not incidentally, the Man confesses that he is a huge fan of the poet's work, and this bit of ego stroking is all the lubrication needed to embed the Man in the house, like a chain-smoking, ill-mannered tick. The next day his wife the Woman (Michelle Pfeiffer) arrives, and she is similarly negligent, brusque, and presumptuous, with a twist of vodka-soaked WASPish venom. The mysterious presence of these strangers is plainly a source of anxiety for the Mother, who gradually grows to feel like an impotent trespasser in her own home. She is eyed contemptuously or outright ignored, and yet somehow, she always seems to be saddled with the work of cleaning up the guests’ heedless messes. (This too becomes a source of hallucinatory horror, as when she glimpses some fleshy Cronenbergian vermin lurking in the depths of a clogged toilet.) Unfortunately, the Man and Woman are only the first of many visitors who will invade the house.

That’s all that it seems prudent to say about “what happens” in mother!, in the plot sense. Increasingly, the film devolves into a symphony of nerve-wracking chaos, as a catalog of humanity’s ugliest impulses slithers and shreds and smashes its way into the house. The third act is one long, jaw-dropping descent into apocalyptic hell, as the Mother is battered bodily by waves of invasion and destruction. The final 30 minutes or so of the film are such an unhinged, uninterrupted spectacle of pandemonium, the viewer will find themselves afraid to blink.

Aronofsky draws inspiration from a range of psychological and supernatural horror films, including those directed by the likes of De Palma, del Toro, Kubrick, and the aforementioned Cronenberg. There’s more than a little of Herk Harvey’s Carnival of Souls in mother!’s lineage, and dribbles of The Conjuring and its ilk as well. The most immediately salient influence, however, is undoubtedly Roman Polanski’s informal “Apartment Trilogy” of horror features: Repulsion, Rosemary’s Baby, and The Tenant. Rosemary’s fingerprints are conspicuous enough that one of mother!’s poster designs is an explicit riff on the iconic poster for Polanski’s 1968 masterpiece, but Aronofsky’s feature touches on motifs and themes from all three films.

One component lifted from Polanski that is vital to mother!’s mood is the anxiety of losing control—not of one's self, but of one’s situation. Like Rosemary Woodhouse, Repulsion’s Carol, and The Tenant’s Trelvoksky, the Mother is reduced to a miserably passive role, swept along by the schemes and appetites of the people around her. However, where Polanski’s vulnerable protagonists are pursued and remolded by others, the Mother is simply ignored. Although mother! is an unabashedly phantasmagorical work, its surreal heights are underlain by a foundation of real-world anxieties. (Women’s anxieties specifically; more on that in a moment.) The film’s horror is rooted in impotence and invisibility: Much of mother! consists of Lawrence screaming herself hoarse at people who simply won’t listen. In isolation, many of the film’s scenes resemble archetypal nightmares about the challenge of asserting oneself and drawing boundaries: There were strangers in my house, eating my food and using my toilets and taking my things, and I shouted for them to leave, but no one paid any attention to me. (In this, the film resembles an inside-out revisionist take on Luis Buñuel’s The Exterminating Angel.)

Aronofsky’s film is so dense with potential allegorical readings, there will doubtlessly be some who accuse mother! of being a hodgepodge of vivid imagery that looks meaningful but doesn’t convey any coherent meaning. The validity of this criticism is undercut by the richness of any individual metaphor the viewer chooses to pursue. Different viewers will gaze into the pulsating depths of this dark prism and see different things, but every vision is stark and terrifying. The possible interpretations are manifold: the monotheistic God as self-absorbed sociopath; the history of human civilization compressed into two hours; the cyclical bedlam of pop culture consumption; or a lacerating portrait of an artist’s self-loathing, to name just a few. These and other readings are all fruitful veins of exploration. (It will fall to other writers to psychoanalyze the film’s seething disgust for the male artistic ego and its need for adulation.)

For this writer, the most evocative approach to mother! is a feminist one. (Confoundingly yet predictably, the film’s righteous loathing for the exploitation of women is already being willfully misconstrued as misogyny in some quarters.) Early in the film, Aronofsky devotes a significant amount of screen time to the Mother’s daily housework and long-term rehabbing projects. Creating the perfect home is manifestly a labor of love for her, but it’s a love that is ultimately channeled towards an (allegedly) Great Man. With almost impressionistic gestures, the film illustrates the colossal effort that the Mother puts into the four-course, Instagram-worthy meals she prepares. It then gracefully draws attention to the way that He swoops in, devours them, mutters his gratitude, and then flits away to devote more time to the writing that his is obviously not doing. No horror film in memory has scrutinized the unacknowledged, uncompensated physical and emotional labor of women with such remorseless resentment. It’s not a portrait of the artist as an abusive brute, but as an ordinary self-absorbed, negligent man.

Despite mother!’s mythic sensibility, the film’s depiction of gender roles is unexpectedly realist, not to mention bitterly critical. Remarkably, this element of modern socio-political commentary is not diminished by the film’s absorption with ghastly gothic motifs or Biblical symbolism. (Adam and Eve, Cain and Abel, Abraham and Isaac, and other Old Testament dyads are frequently alluded to.) If anything, they lend mother! an added dose of “same as it ever was” pessimism. This sentiment is underlined by the way the film ultimately loops in on itself—much like The Tenant, as it happens—suggesting a never-ending cycle of exploitation.

Aronofksy’s film will likely be a deeply uncomfortable experience for some male viewers. Part of that discomfort is visceral, stemming from how closely the film follows the Mother’s viewpoint as she endures a marathon of psychological and physical mortification. (Reverse Maniac, one might call it.) However, as with Richard Yates’ blistering novel of midcentury discontent, Revolutionary Road, what truly disturbs about mother! is how easy it is to discern oneself in the entitled, churlish male characters. It’s psychologically repellent in a way that hurts, and it hurts because it contains a sliver of truth. In mother!’s nightmarish conception, patriarchy isn’t so much a despot as a gluttonous maw, devouring everything that women can give: their labor, support, attention, adulation, bodies, and children. When there’s nothing left, it tosses them aside and reaps all the rewards (and credit) for their invisible contributions. Male power is, counter-intuitively, portrayed as a lumbering succubus.

The sinewy intelligence of mother! lies in its astonishing capacity for nuance, despite its garish and gory metaphors. Underneath the film’s thick slathering of terror and rage, Aronofsky conveys the myriad complicating dynamics that make patriarchy a lumpy slurry of dispiriting grays rather than a black-and-white tale of male villainy. At various points, mother! touches on the way that women can be revered even as they are exploited; on women’s participation in and perpetuation of misogyny; and on the vicious, mercurial criticisms directed at women who are public figures. (Including celebrities like—wait for it—Jennifer Lawrence.)

None of this is to say that Aronofksy’s film doesn’t invite other, equally compelling readings. Nestled within mother! is a desolate parable about the birth, life, and death of works of art, to cite just one example, and that story dovetails with its feminist outlook in evocative ways. Nor is it the case that a feminist interpretation is entirely fitting. There are a handful of frustrating gestures that undercut this reading, such as the Mother’s eventual willingness to play the role of a selfless, self-annihilating martyr. What’s so stimulating about mother! is that it invites this sort of reflection rather than demanding a clear-cut reaction. Its ideas are emergent rather than painted-on, which makes it doubly frustrating that it’s exactly the sort of film that will inevitably (and inaccurately) labeled as pretentious. Pretense implies an arrogant intellectual posturing that weakens a film’s principal obligation to tell a compelling story. mother! is just the opposite. In the moment, it's a riveting work of cinema that rattles the senses. In the days and weeks that follow, it urges the viewer to ruminate on what exactly they glimpsed in that whirlwind of blood and fire.

It's slippery in here.

[Note: This post contains spoilers.]

Twin Peaks: The Return // Parts 17 and 18 // Original Air Date September 3, 2017 // Written by Mark Frost and David Lynch // Directed by David Lynch

As was observed in this blog’s first post on Twin Peaks: The Return, the bleak Season 2 finale of Mark Frost and David Lynch’s original, groundbreaking show may or may not have been originally intended as the series finale, but it certainly feels more like a semicolon than a period. The same cannot be said of the finale to Twin Peak: The Return. Whatever one’s theories regarding the meaning of the new series’ final episodes, and notwithstanding what seem like dozens of unresolved questions and abandoned subplots, it absolutely feels like an ending. Just not the ending that viewers may have expected or wanted.

Like the first two episodes of the series, Parts 17 and 18 of The Return were aired back-to-back on the same night. Unlike Parts 1 and 2, the final two chapters virtually demand to be contemplated in relation to one another. In some ways, Part 18 resembles a rebuttal to Part 17 (and to the entire series). In the context of The Return’s sprawling, digressive bulk, it is indisputable that the finale resolves very little. (What has become of armpit rash girl? Or Beverly’s dying husband? Or Audrey fucking Horne??) Yet Part 17 has the unmistakable air of a narrative conclusion to the previous 16 hours. It is plainly a crescendo in which numerous characters converge for a climactic showdown and minor plot points come to long-delayed fruition.

The final defeat of Dale Cooper’s malign double Mr. C (both Kyle MacLachlan) and the otherworldly entity BOB (the late Frank Silva) unfolds like an early, low-budget X-Files episode filtered through art film sensibilities. Not only is the viewer given atypically gratifying payoff for story elements as diverse as the Great Northern Room 315 key and Deputy Andy’s prophetic visit to the White Lodge, but the supernatural villains are dispatched in a strangely straightforward manner. Mr. C is shot and killed by none other than sweet, guileless receptionist Lucy Brennan (Kimmy Robertson). Meanwhile, after emerging from Mr. C’s abdomen as a floating orb of putrefaction, BOB is literally punched to smithereens by Freddie (Jake Wardel) and his miraculous green gardening glove. Of all the fates one might have envisioned for Twin Peaks’ unearthly boogeyman, metamorphosing into a volleyball from Hell and then being walloped into oblivion by a super-powered Englishman was likely not high on the list.

BOB’s demise is so ridiculous and tonally jarring that the scene seems to have been plucked from another show, or even from a work of not-terribly-good Twin Peaks fan fiction. Is it really the case that the show’s embodiment of ravenous, corrupting evil can be obliterated with a powerful right hook? Combined with the worlds-collide uncanniness of seeing, say, Sheriff Truman (Robert Forster), Tammy Preston (Chrysta Bell), and Bradley Mitchum (James Belushi) in the same room, the sheer Evil Dead absurdity of the villains’ defeat gives the showdown the atmosphere of a fever dream about some other television show. For Twin Peaks—and especially for The Return—it all feels uncommonly neat and tidy, as exemplified by Candie’s (Amy Shiels) breathless glee that the Mitchum entourage has brought enough sandwiches to feed this sudden assemblage of characters.

However, David Lynch provides an unmistakable sign that this discordance—the ill-fitting piece crammed into place as a jigsaw puzzle nears completion—is not only intentional, but the symptom of a more profoundly disquieting idea. This the director achieves through a small but provocative gesture, superimposing Dale Cooper’s confused and faintly distressed face over the aftermath of the confrontation. Even as Cooper reunites with his former assistant Diane (Laura Dern) and quickly brings the gathered characters up to speed on what is happening, his own uneasy countenance hovers, Great Oz-like, over the scene, as though it were a reverie in Coop’s mind. Underlining the point, the FBI agent abruptly observes in an unsettling, slowed-down voice, “We live inside a dream.” (But who is the dreamer?) He also discerns that the time on Sheriff Truman’s office clock is fluctuating between 2:52 and 2:53, the latter summing to the “number of completion” described in Cooper’s earlier message to Gordon Cole. The world seems to be stuck on the brink of a gravid moment.

The victory against Mr. C and BOB is complete, but, unfortunately for all involved, this is not a sufficiently satisfying conclusion as far as Cooper is concerned. By way of the locked door in the bowels of the Great Northern, he enters the meeting place above the unearthly convenience store to confer with Philip Jeffries (Nathan Frizzell), still puffing away in the form of a teapot-like electric contraption. With Jeffries’ assistance, Cooper travels across time and space to the early morning hours of February 24, 1989, the proverbial ground zero for the violent tragedy that originally brought him to Twin Peaks.

In a scene that is amusingly reminiscent of Back to the Future II, he secretly observes events previously portrayed in Fire Walk with Me, and then waylays Laura Palmer (Sheryl Lee) on her way to rendezvous with Leo Johnson and Jacques Renault. Cooper attempts to lead her by the hand through the forest and away from her fate, and in the process unravels 25 years of history (both in Twin Peaks the town and on Twin Peaks the show). Laura’s plastic-wrapped corpse flickers and vanishes from the riverbank near the Packard sawmill. Thrown into a howling, demonic rage, the entity that occupies Sarah Palmer’s form savages Laura’s framed homecoming photo with a broken bottle, but the image stubbornly refuses to remain mutilated. For a moment, it seems as if Dale Cooper has achieved the impossible and saved Laura Palmer. And then the floor drops out: Laura vanishes with a scream.

This is where Part 17 ends, and where Lynch shifts gears into a prolonged, listless epilogue, mutating the final hour of The Return in something bizarre, unpredictable, and inexplicably frightening (more so than usual). Cooper emerges from the past, apparently thwarted in his attempt to rescue Laura, and is greeted at Jackrabbit’s Palace by Diane. The pair of them then journey to an alternate portal several hundred miles away, along the shoulder of a highway and underneath some humming power lines. Cooper observes that “once we cross, it could all be different,” and they share a kiss before literally driving their car through the gateway.

The world that they enter is not the Black Lodge, or White Lodge, or some other surreal supernatural locale. Rather, they find themselves on an ordinary nocturnal highway leading to an equally ordinary desert motel. They secure a room and proceed to have uncomfortably detached sex as the Platters croon “My Prayer” on the soundtrack. (Intriguingly, this is the same song that was playing in Part 8 when the New Mexico radio station was commandeered by the Woodsman.) In the morning, Cooper is alone, finding a goodbye note in which Diane weirdly refers to him as “Richard” and to herself as “Linda.” Even more strangely, Cooper discovers that the hotel and his car now look completely different, and that he is in the town of Odessa, Texas.

What follows resembles a plodding, Lynchian riff on a stark Western crime thriller. (The setting is significant: In Cormac McCarthy's No Country for Old Men, Odessa is where Llwelyn Moss sent his wife Carla Jean to keep her safe during his looming confrontation with the homicidal Anton Chirugh.) Guided predominantly by instinct, Cooper tracks down Laura Palmer, or at least a woman who he believes to be Laura Palmer. (He does take the time, however, to teach some leering wannabe cowboys a lesson for harassing a waitress, as if he were the brutally righteous, new-in-town lawman in a John Ford film.) The woman he finds, Carrie Page, is indeed a dead ringer for a middle-aged Laura. Even though she claims to know nothing about the girl Cooper is seeking, the name of Sarah Palmer seems to resonate with some faint memory in Carrie’s subconscious. Leaving the presence of a dead body in her living room pointedly unremarked-upon, she agrees to travel with Cooper to Twin Peaks.

A lengthy, mostly wordless passage then unspools, in which Cooper and Carrie drive through the night from Texas to Washington. Sporadically, the drone of the interstate is broken by another car’s dogged headlights (“Are we being followed?”) or by weary non-sequiturs from Carrie. Time seems to slip away ambiguously and eventually the pair arrive in Twin Peaks. Carrie attests that she recognizes nothing, but Cooper nonetheless drives her to the Palmer house. There, to Cooper’s confusion, the door is answered by a woman named Alice Tremond (Mary Reber), who has never even heard of Sarah Palmer. This revelation seems to jostle Cooper’s awareness that his situation is profoundly wrong somehow, and both he and Carried stand before the Palmer house in a daze of mounting apprehension. “What year is this?,” Cooper asks fearfully, almost to himself. From within the house, Carrie hears Sarah’s faint, distorted voice (“Laura!?”). Then she begins to scream, and the world plunges into darkness.

For Twin Peaks devotees who assiduously steeped themselves in the 18 hours of The Return in the hope that Dale Cooper would emerge victorious and goodness would be restored (at least in some small way), there is doubtlessly understandable frustration, even anger, with the show’s conclusion. A viewer could be forgiven for feeling aggravation that Mark Frost and David Lynch have succeeded in fooling them again, like Lucy yanking the football away from Charlie Brown at the last minute. Once again, the audience is denied answers to their nagging questions. Once again, the hero who is “supposed” to win is bested by the forces of darkness. Once again, Twin Peaks spends its last episode indulging its most cryptic tendencies instead of resolving plot threads.

However, as the saying goes: fool me twice, shame on me. If a viewer settled into The Return with the expectation that their questions would be satisfactorily answered—let alone that they would witness anything remotely like a happy ending—they have no one to blame but themselves. The Return’s devastating, seditious conclusion is not only consistent with the finale of the original series, but also with David Lynch’s post-Peaks filmography. Dale Cooper’s foray into Carrie Page’s “sideways universe” (to borrow from the Lost lexicon) bears a strong resemblance to the uncanny alternate realities encountered in Lynch’s Lost Highway / Mullholland Drive / Inland Empire triptych. What’s more, the horror of consciousness and perception that underlies these illusory universes has been at the heart of The Return from its first scenes. (Is it future or is it past?) The surprise is not that Frost and Lynch essentially unraveled the fabric of their show in the end, but that viewers ever expected a conventional television drama wrap-up from the creators that gave the world the blood-smeared giggle of “How’s Annie?”

Doubtlessly, every jot of The Return will be obsessively scrutinized in the years to come, with much attention paid to the film’s final episode and how it retroactively changes the preceding 17 hours. Certainly, there are plentiful clues in the text that permit study and exegesis, such as a curious proliferation of pale horses. However, given that, 40 years later, there are still fragments of Eraserhead that remain stubbornly inscrutable, it seems doubly pointless to rush forward to decode every detail. (“Break the code, solve the crime,” has always been Twin Peaks’ fundamental lie.) Like all of David Lynch’s work, The Return is not completely impenetrable to reason, but it cannot be adequately assessed unless the emotional responses it elicits are acknowledged and examined.

There is so much warmth to be found in The Return—humor, splendor, and excitement—one is hesitant to focus exclusively on the fears it explores, or worse yet, to reduce its staggering breadth to a single moment of elemental terror. What cannot be denied, however, is that the potency of the series' concluding moments are founded on the preceding 18 hours. Without arm wrestling and golden shovels and frog-locust things and a boxed cherry pie and all the rest, the annihilating darkness of Part 18’s last breath is not nearly as potent in its door-slamming finality.

In Béla Tarr’s brutally nihilistic masterpiece A Turin Horse, the resigned sigh that concludes the film is predicated on 140-plus minutes of repetition and hopelessness. The former achieves its apocalyptic power through the latter. Similarly, Laura Palmer’s final shriek of terror in Part 18 of The Return is the stuff of nightmares, not only because of Lee’s singular scream (Jesus, that scream), but because it punctuates a massive work that repeatedly expresses the anxiety of depersonalization (the unreal self) and derealization (the unreal world).

In part, The Return’s interest in such fears lies in their psychological ramifications in the real world. Notably, Audrey’s mysterious plight illustrates how easily unreal sensations can spiral into a panicked, paralyzing existential crisis for those suffering from anxiety disorders. However, The Return is particularly preoccupied with the unreality of dreams, fantasy, and fiction—and to what degree such ephemeral worlds can be thought of as “existing” at all. It’s perhaps intellectually precarious to advance a Grand Unified Theory of Twin Peaks: The Return at such an early date. However, this theme is undeniably essential to an appreciation of Frost and Lynch’s idiosyncratic and shrewdly metafictional approach to the very idea of a Twin Peaks revival. At risk of sounding glib, The Return is a show about itself. It is concerned with creation, consumption, television, television shows, television show revivals, audience expectations, the emotional ownership of fiction, and the “realness” of fictional people and worlds.

That last item is a recurring thematic element in The Return, but in Part 18 it takes center stage. If Fire Walk with Me can be regarded as David Lynch’s effort to restore Laura Palmer’s humanity and agency, The Return is a corrective in the other direction: an acknowledgement that Laura Palmer is a construct, doomed to follow the dictates of her dual Cartesian demons, Frost and Lynch, for the entertainment of millions. Although the viewer knows Who Killed Laura Palmer in the proximal sense, the query persists in other forms, leading the questioner down rabbit holes both mythological (Is Judy ultimately responsible for her death?) and extra-textual (Is David Lynch responsible?). Perversely, by asking the question, the viewer is obliged to murder Laura Palmer all over again. By reviving their television series after 25 years, the creators are exhuming her corpse, breathing life into her, and then once again allowing her to be murdered, millions of times over. She must be murdered, or, as when Cooper takes 18-year-old Laura's hand in the woods, Twin Peaks the show will become something unrecognizable. (Not Twin Peaks?)

Twin Peaks is not merely about Laura Palmer the murdered girl and the Dale Cooper the FBI agent, but also about "Laura Palmer" and "Dale Cooper," the characters on the television show Twin Peaks. Regardless of whether one views the sideways universe of Odessa, Texas in Part 18 as an alternate timeline, a sanctuary dimension, a demonic prison, or whatever else, it is not where Laura and Cooper are “supposed” to be. It is Not Twin Peaks. They sense it, deep within their (nonexistent) bones, that something is not right. Twin Peaks has its own gravitational field. Like water flowing downhill or iron filings skittering towards a magnet, Dale Cooper will always seek out Laura Palmer, alive or dead, no matter what names they go by in any given reality. Dale will always be the questing detective, and, as the corpse in Carrie’s house attests, Laura will always be the archetypal Lynchian “Woman in Trouble”.

Confronted with the façade of the Palmer House and an echo of her mother’s voice, Carrie suddenly comprehends who she is. She’s the girl who’s full of secrets, the murdered homecoming queen, the body wrapped in plastic. She has been abused, raped, and murdered by her father countless times, and will be again, for eternity. She screams when that glut of garmobonzia, the pain and sorrow, comes flooding back. However, she also screams because she understands a deeper, sanity-splintering truth. “What year is this?” Cooper asks, but he’s not truly asking about the date. He’s asking, “How did I get here? How do I work this? Am I right? Am I wrong?” In that moment of comprehension, he has achieved an awful enlightenment: He is living in a dream (a television show), but he is not the dreamer. Neither is Laura. They are tulpas, projections of the minds of Mark Frost and David Lynch. They are manufactured.

Pronouncing that a book is “unfilmable” is a dicey move, if only because it’s proven to be such a flimsy label. Over the decades, allegedly intractable works ranging from Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy to William S. Burroughs’ Naked Lunch have inevitably yielded to filmmakers who found an appropriate, often unconventional angle of approach for the material. If such eccentric “anti-novels” can be molded into narrative cinema, then certainly an evocative pulp horror masterpiece like Stephen King’s It can make the leap from book to screen. Nonetheless, the novel form is so essential to the potency of It as a redolent, rambling work of doelful fiction, any attempt to adapt the story to film faces an uphill battle.

Of course, King’s novel has been adapted, first as a two-part television miniseries originally broadcast on ABC in 1990 and now as a two-part theatrical feature helmed by Argentine director Andrés Muschietti. However, it is arguable whether either work constitutes a successful adaptation of King’s tale. The question is not whether It’s bulk can be squeezed into three or four hours of cinematic storytelling, but whether one should. A colorable argument could be made that the deformations necessary to achieve this translation necessarily turn the story into something markedly divergent (Not-It?). The debacle surrounding The Lawnmower Man—wherein a pagan-themed short story penned by King was rather bafflingly transmogrified into a hokey science-fiction thriller—illustrates that a shared title is no guarantee that the source material will be even remotely honored by the filmmaker.

Certainly, director Tommy Lee Wallace’s three-hour 1990 telefilm was generally faithful to the novel while also making quite an unforgivable hash out of it. The blame can’t be laid entirely at the feet of Wallace and co-writer Lawrence D. Cohen, however. The series was positioned to fail from the beginning, given its constraints: the PG-13-level content restrictions of network television; a budget that was far too meager to fulfill the story’s ambitious scope; the limits of visual effects technology in 1990; and the commercial necessity of appealing to a mainstream prime-time audience assembled in their living rooms.

Purely in terms of polish, Muschietti’s film is playing in a league several levels above that of the 1990 miniseries. The formal aspects of It’s latest incarnation—particularly the cinematography, production design, and visual effects—are executed at the high level one expects of a wide release horror film based on a cherished property. The performances are also superior, anchored by a charismatic cast of child actors whose work here ranges from solid to downright dazzling. However, these assets do not necessarily equate to a first-rate adaptation. In terms of translating the staggering emotional robustness of King’s masterwork, Muschietti’s It is a double rather than a home run, but still a heartfelt, handsome, and feverishly spooky work of cinema.

The Stand or the Dark Tower series are perhaps more likely to be cited as Stephen King’s magnum opus, but It is a singular achievement, arguably the closest the author has ever come to bridging the divide between a genre lit page-turner and the Great American Novel. Fundamentally, It is a midnight monster movie as a Bildungsroman. Over the course of the summer of 1958, seven 11-year-old misfits in the town of Derry, Maine develop a friendship. Gradually, the members of this self-styled “Loser’s Club” of tween outcasts discern that they are each being terrorized by the same shape-shifting monster, an entity that feeds on fear. Eventually, the Losers delve into the creature’s subterranean lair and destroy it, or so they believe. Here King effectively puts the standard coming-of-age tale on pause for 27 years, as the Losers grow into successful (yet troubled) adulthoods, move away, and gradually forget their harrowing experience. Eventually, the monster resurfaces, compelling the now middle-aged Losers to return to Derry and reunite, with the goal of eradicating the malevolent “It” for good. (There is, needless to say, quite a bit of subtext in King’s novel regarding the arrested development and unsettled traumas of the Boomer generation.)

Despite its extensive cast of characters, recurrent digressions, and 1,000-plus-page length, It is not truly a sprawling epic in the same vein as The Stand. Most of the novel’s events unfold over a relatively short period (one summer in 1958 and a few days in 1985), and the action is confined primarily to Derry and its surroundings. However, the scale of the book feels enormous, in the same way that a momentous summer vacation can dilate in one’s memories until it achieves a Tolkien-level mythic density and moral starkness.

In part, this is due to King’s customary attentiveness to the nuances of setting—more evocative in It than anywhere else in his work—as well as his fulsome yet agile engagement with the points-of-view of secondary and tertiary characters. It’s most conspicuous formal feature, however, is doubtlessly its hopscotching structure. The author leaps back and forth in the story’s chronology, entwining the past and present in a way that not only reflects the psychological realities of trauma, but also examines the bizarre gestalt of reverence and denial that characterizes American attitudes towards history.

This is one rare respect in which the 1990 miniseries more closely follows the source material than does Muschietti’s film. Opting for the most blunt and reductive approach to such a massive story, Warner Bros. has elected to split the novel’s events into two discrete halves, one depicting the Losers as children, and one revisiting them as adults. This straightaway removes one of the novel’s most distinguishing features, although given the clumsy way the prior adaptation handled the two timelines, perhaps it’s for the best.

The first of the new It films is accordingly the story of the Losers’ initial confrontation with Derry’s protean boogeyman. The screenplay pushes these events forward from 1958 to 1989, which allows the studio to set the second feature film in the present day. (A-level production design naturally being cheaper for one period piece than for two such films.) Not incidentally, this approach also places the first film squarely within the formative years of today’s middle-aged viewers, the exact cohort that snuck first-edition copies of the notoriously violent and sexually explicit It off their parents’ bookshelves.

Muschietti is blessed with a sharp ensemble of child actors in the roles of the seven Losers: lanky stutterer Bill Denbrough (Jaeden Lieberher), the group’s informal leader; home-schooled African-American farm boy Mike Hanlon (Chosen Jacobs); obese, bookish “new kid” Ben Hanscomb (Jeremy Ray Taylor); scrawny, hypochondriac Eddy Kaspbrak (Jack Dylan Grazer); impoverished tomboy Beverly Marsh (Sophia Lillis); bespectacled wiseass Richie Tozier (Finn Wolfhard); and rabbi’s son Stan Uris (Wyatt Oleff), the group’s anxious skeptic. As the nominal lead and the sole Loser with a personal vendetta against It—the creature abducted his little brother George one year prior—Lieberher's Bill is given more screen time than the others. Unfortunately, consistent with the novel and the 1990 miniseries, Mike and Stan are not as well-characterized as the other five Losers, and Jacobs and Oleff consequently don’t leave a strong impression, through no particular fault of their own. That said, there isn’t an obvious weak link in the bunch, performance-wise, although there are some standouts. Wolfhard absolutely runs away with every ensemble scene, tossing profanity-strewn insults and dirty jokes in the exact manner of a junior high class clown who’s trying a bit too hard. Lillis is the real discovery, however, a sparkling presence who shifts smoothly and convincingly between Beverly’s two poles: sharp-tongued, quick-witted tough girl and cringing, conciliatory abuse victim.

The Losers are It’s heart and soul, but the star of the show is, of course, Pennywise the Dancing Clown (Bill Skarsgård), the grease-painted shape that It seems to prefer when hunting Derry’s children. The new film’s frilly, 19th-century design for Pennywise is far afield from the Bozo-like figure described in the novel and featured in the miniseries. There’s a little Pagliacci and commedia dell'arte in the costume as well, and the overall impression is distinctly fusty and effeminate, as though Pennywise were a life-sized doll who had clambered from some Victorian child’s toy chest. Physiologically, there is something distressingly abnormal about the clown, as evinced by his bulbous forehead, rodent overbite, and unruly eyes that never quite seem to follow each other perfectly. In short, he’s creepy as hell, but he also seems a bit too obviously designed to be creepy, which would seem to undercut the entire point of a “friendly clown” façade. In short, this Pennywise looks like a horror movie perversion of a clown, not an actual clown that one might find twisting balloon animals at a fair. Just as it’s difficult to imagine any little girl voluntarily choosing to play with the Annabelle doll, one can’t envision any right-minded child approaching Skarsgård’s Pennywise, unless they were dragged there kicking and screaming.

Skarsgård’s performance will inevitably be compared to that of Tim Curry, who portrayed Pennywise in the 1990 miniseries, but their takes on the character are so divergent it’s hard to assess them side-by-side. Curry’s approach to the clown was devilishly campy but perhaps too human, his croaky threats sometimes wandering away from “puffed-up Disney villain” and into “angry, abusive gym teacher.” In contrast, Skarsgård portrays Pennywise as a restless bundle of childish giggling, snorting, and muttering, as though he were a demonic Little Lord Fauntleroy working himself into a fit over a promised sweet (or a kitten to burn). It’s such an outrageously high-strung performance that it takes a minute or two for the viewer to attune themselves to Skarsgård’s unstable wavelength.

This sort of over-the-top portrayal pays unexpected dividends, however, when one starts to pick up on the subtleties that Skarsgård doodles between the lines. At times, Pennywise abruptly seems to glaze over or lose track of what he is saying, as though he had gone into momentary mental vapor-lock. It’s the huge red, toothy smile that truly unnerves, however. It mostly alternates between a naughty-boy leer and a manic Joker grin, but occasionally something more disturbing peeks through, as though an alien were attempting a hideous approximation of a human smile. Such cues suggest that for all It’s predatory cunning and supernatural insight into its victims’ fears, there is some elusive aspect of humanity that It is not able to emulate.

The film’s screenplay is credited to Gary Dauberman, Chase Palmer, and Cary Fukunaga, the latter attached to direct until he allegedly parted ways with the studio over that old chestnut, creative differences. However, the result is still a snug story, lacking the palpable seams that would indicate numerous script overhauls. If anything, It’s most conspicuous flaw is that it feels too streamlined, pitilessly compressing events that took hundreds of pages to unspool in King’s novel. The author’s notorious verbosity notwithstanding, the time spent slowly steeping in the exuberant and harrowed lives of the Losers is essential to the book’s appeal. The reader grows to know and love this gaggle of misfit kids—and then to fear that, for all their bravery and planning, they are still alarmingly outmatched by the monster.

In comparison, Muschietti’s film has expurgated the story to the point that its emotional foundations feel noticeably undernourished. The plot isn’t perfunctory so much as hasty and graceless, with an outline that could be scrawled out on a cocktail napkin. The film introduces the Losers, and then serves up roughly one scary set piece per kid. They quickly piece together what’s going on, and thereafter head into the sewers to slay the proverbial dragon. Intertitles attest that the film’s events take place over three or four months, but there doesn’t seem to be any practical reason It should take that long to unfold. Given the simplicity of the film’s A to B to C trajectory and the ruthlessness of the pruning performed on the source material, it’s a two-week story, tops. Of course, it would have been preferable if the filmmakers simply hadn’t condensed the plot so aggressively to begin with. One can envision a cinematic adaptation that would allow King’s story the necessary breathing room to achieve its full emotional and spiritual potential, but that film is an 8- or 12-hour limited series, rather than a pair of theatrical features.

Some of the minor revisions made in the transition from novel to screenplay are puzzling. The Losers are one or two years older than they are in the book, a change that slightly but meaningfully alters the story’s wistful tone, not to mention the dynamic between Beverly and the boys. Similarly, the film leans a bit more strongly than the novel did on the unspoken romantic triangle between Bill, Beverly, and Ben. The film does not derive any discernible benefit from such alterations to King’ story, which raises the question as to why they were made in the first place.

(The only excision that is obligatory is the removal of the so-called “kiddie-kiddie-bang-bang”: the notorious, gratuitous, thankfully non-explicit passage in which 11-year-old [!] Beverly decides, apropos of nothing, to have sex with each of the other Losers. It’s a horribly misconceived scene of jaw-dropping bad taste, pushing King’s novel dangerously into child pornography territory.)

While It’s story weaknesses are hardly insignificant, Muschietti and his crew unequivocally deliver when it comes to horror fundamentals. The creepy, rattling set pieces in which Pennywise takes repulsive delight in scaring the absolute beejeezus out of the Losers are terrific stuff. Strictly speaking, these sequences aren’t exactly scary. A seasoned horror aficionado will see every jump coming, and, with a few exceptions, the film doesn’t employ any tricks that haven’t been used before, in countless monster flicks and ghost stories.

What’s exceptional about It is that the film manages to make it scares such delicious fun, in the style of a first-rate haunted house. Appropriately enough, the overall tone of Pennywise’s approach is that of the over-enthusiastic player in a R-rated carnival funhouse. The Losers themselves are unequivocally terrified by It’s illusions, which often reflect their deepest fears. However, the viewer’s reaction is likely to be anxious tittering and exhilarated screams, accompanied by the vaguely pleasurable gooseflesh that a spooky campfire story elicits. The central achievement of Muschietti’s film is that manages to be a thoroughly entertaining horror tale without ever losing the novel’s essential atmosphere of hyper-real childhood dread and suffering.

This version of It is very much in the vein of Sam Raimi and Tim Burton, on those occasions when their work wriggles ambiguously in the murky space between horror and comedy. A scene where Ben is chased through the stacks of the Derry library by the headless, smoldering corpse of a child is pure Evil Dead in the best possible way, in that the viewer doesn’t know whether to laugh nervously or scream delightedly at the apparition’s herky-jerky movements. This slightly ridiculous, even kooky sensibility doesn’t detract from the film in the least. Indeed, it’s perfectly aligned with the way that an intense nightmare inevitably sounds silly when the dreamer later tries to explain why it undid them so thoroughly.

Funhouse scares are It’s most obvious strength, but it isn’t the only game the film knows how to play. Muschietti gradually allows a more explicitly alien horror to peek through the literal cracks in Pennywise’s mask, most memorably glimpsed in the gaping, needle-toothed Lovecraftian maw that he sometimes reveals. The film’s R rating allows Muschietti to indulge in some striking gore—as well as visceral violence perpetrated against children, normally a horror taboo—but what lingers most intensely is the terror of the grotesque. Pennywise is consistently creepy when on screen, but his most searing moments occur late in the film, when his façade begins to peel away in eruptions of spasmodic limbs, noxious excretions, and blubbering screeches. The Losers’ final confrontation with It echoes The Thing, The Fly, and even Terminator 2, as Pennywise oozes and shudders through his numerous forms, some of them previously seen by the kids and some suggesting more monstrous, unfamiliar morphologies.

It generally relies on standard horror film tropes—scary clowns, decrepit houses, fetid sewers, shambling corpses—although it executes those familiar elements with prodigious style. Much of the credit should go to Korean cinematographer Chung-hoon Chung, a frequent collaborator with Chan-wook Park. Granted, nothing in It approaches the dazzling visuals of Park’s best features. After last year’s sensual, phantasmagoric The Handmaiden, also shot by Chung, Muschietti’s film almost looks drab. However, virtually every shot in It is a handsomely composed little marvel, whether it’s a sun-kissed snapshot of summer horseplay or a trembling look down a moldering subterranean passage.

Like Muschetti’s dour, muddled first feature, Mama, the film relies a little too much on a dank, putrefied aesthetic, but at least here it’s justified (Pennywise is a sewer monster, after all), and blessedly balanced with the warm, vitalizing colors of a New England summer. Although Muschietti and Chung are generally dependent on King’s novel for their set pieces, they find ways to visualize some key elements (e.g., the mesmerizing “deadlights” that Pennywise controls) in innovative ways. Occasionally, they even discover a strikingly original vista. Chief among these is Pennywise’s lair, a cavernous vault of gothic rot with a breathtaking centerpiece straight out of Guillermo del Toro’s twisted imagination. Around a hundred-foot tower composed of waterlogged childhood detritus—clothes, toys, books, bikes—a slow-motion maelstrom of little bodies float in midair, a trophy display for Pennywise’s discarded, fear-sapped victims. It’s the kind of chilling, spectacular image that almost justifies this cinematic adaptation of It all on its own.